Catriona Robertson photographed for the Robert Walters Art Prize 2021 by Reece Straw

Photo courtesy of the artist

Damaris Athene: Could you start off by introducing yourself please Cat?

Catriona Robertson: Sure, I'm an artist working across sculpture, installation and occasionally performance. I tend to make quite large scale pieces, but recently I’ve been trying to develop fragments of larger scale pieces, smaller pieces as well. I graduated from Royal College of Art in 2019 in sculpture. I live and work in London and have been here for quite a long time, but my family is from up north, Scotland and Oldham and I grew up in Surrey. I moved to London to do my Bachelors in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins. Now I’m a part-time sculpture technician at Central Saint Martins. I've always worked with materials and love learning different processes and I really enjoy teaching alongside my practice.

DA: What a great job to have! Could you say a bit more about your practice?

CR: I've done quite a few residencies over the years where I've made work in response to a particular place, influenced by the architecture, geology and its materials. I can draw from those ideas and take them to different places as well. I’m currently doing a residency in the Lake District at the Merz barn. It's connected to the German Dada artist Kurt Schwitters. His works are very much rooted in destruction, fragments and collecting waste residue materials to make collage and architectural installations such as his famous Merz Bau. I also tend to use a lot of residue, detritus and rubble in my work and I collect found materials - sometimes organic materials like digging clay, or building or domestic materials like corrugated roofing, carpet or lino. In this residency at the Merz Barn I'm responding to the storm damage across the lake district from the storms we had this year and the debris of fallen trees. This damage is partly due to soil erosion, and a number of other factors such as the land being prone to scarring due to the agricultural practices and the history of industries of the area. Trees were chopped down to clear the land which left the remaining woodland vulnerable. The network of trees was disrupted and vulnerable to disease. Now I'm looking at all these uprooted trees everywhere which are pretty monumental. Everything is horizontal and loads of slate has been pulled up entangled in the earth roots that stand as upright as if stone walls. I'm starting to think about the underground and I’m going to build my wormy columns again. There's a connection with this idea of these worms rejuvenating soil and kind of bringing it back to life, but also the history of Roman ruins and columns at the same time. These two connected ideas have developed over time, because originally, I didn't think of the sculptures as worms until the structures started to bend and collapse. There's a connection to regurgitation of materials as the worm absorbs detritus on its outer shell and I imagine it transforming these synthetic materials. When I did another residency with Proposition Studios last year, I started to think a lot about ideas of an urban strata that has been formed in the Anthropocene, with landfill and chemicals and waste being put into the ground. What kind of new sediment is being formed? What kind of rock or stone might have emerge in 1000s of years? From these ideas my sculptures narrate remnants of future monuments that are made up of these waste materials, that take on this anthropomorphic form of the worm that eats these materials, it's become quite gargantuan. It's been a journey in a sense of the work itself that keeps transforming and growing. When I was in art school, I felt pressured to make something new every week. Now I enjoy just letting it flow from one piece to the next.

Rock Paper Scissors, 2020, Paper-clay, papier-mâché, paper-concrete, re-claimed timber, plywood, 50cm x 55cm x 242cm, Photo: Catriona Robertson

Standpoint Gallery, Mark Tanner Sculpture Award Graduate residency

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: Where did the worms and columns originally come from?

CR: The original column started during a different residency in Oslo in 2018. The theme of the Oslo residency really spoke to me, to make something that was monumental and temporal out of waste materials. They took us to the recycling centre where I collected a lot of materials that looked a bit like stone to me, such as Lino flooring that had a stone print on it and grey coloured carpet tiles. I found the corrugated sheeting there that I started using as well to cast concrete panels. It sparked this idea of the corrugated sheeting referencing a Doric column, and I had the idea of this material that is used as a temporary shelter meeting the monumental symbol of the column. I had to build it very quickly, in about five weeks. It was quite strange to build something so monumental that was then taken down again. I find that my work only exists in the space that I install it in for a moment in time that refutes the concreteness of sculpture. Residencies can make you think quickly!

DA: They’re like a pressure cooker! What initially drew you to work with sculpture and installation?

CR: I'm not sure. I remember my art teacher in 6th form college told me I wasn't allowed to make a sculpture because there wasn't enough space. I started smashing up old sinks and things and attaching things to my canvas and I made these really heavy paintings. When I applied to go to art school in London, I sort of accidentally ended up in sculpture. I had actually applied to Fine Art at Chelsea College of Art but they rejected me. My tutor said, ‘You should apply to Central Saint Martins’. So I did and got a place in the 3D pathway that felt right. I really enjoyed it and I loved being in the workshops. I wanted to learn as much as possible. I had a gap between my BA and MA before going to the Royal College of Art. I think it was really important to take some time to gain life experience. I spent a lot of time in Berlin and was a bit obsessed with visiting abandoned buildings, so I think that influenced my ideas about erosion and nature reclaiming the urban.

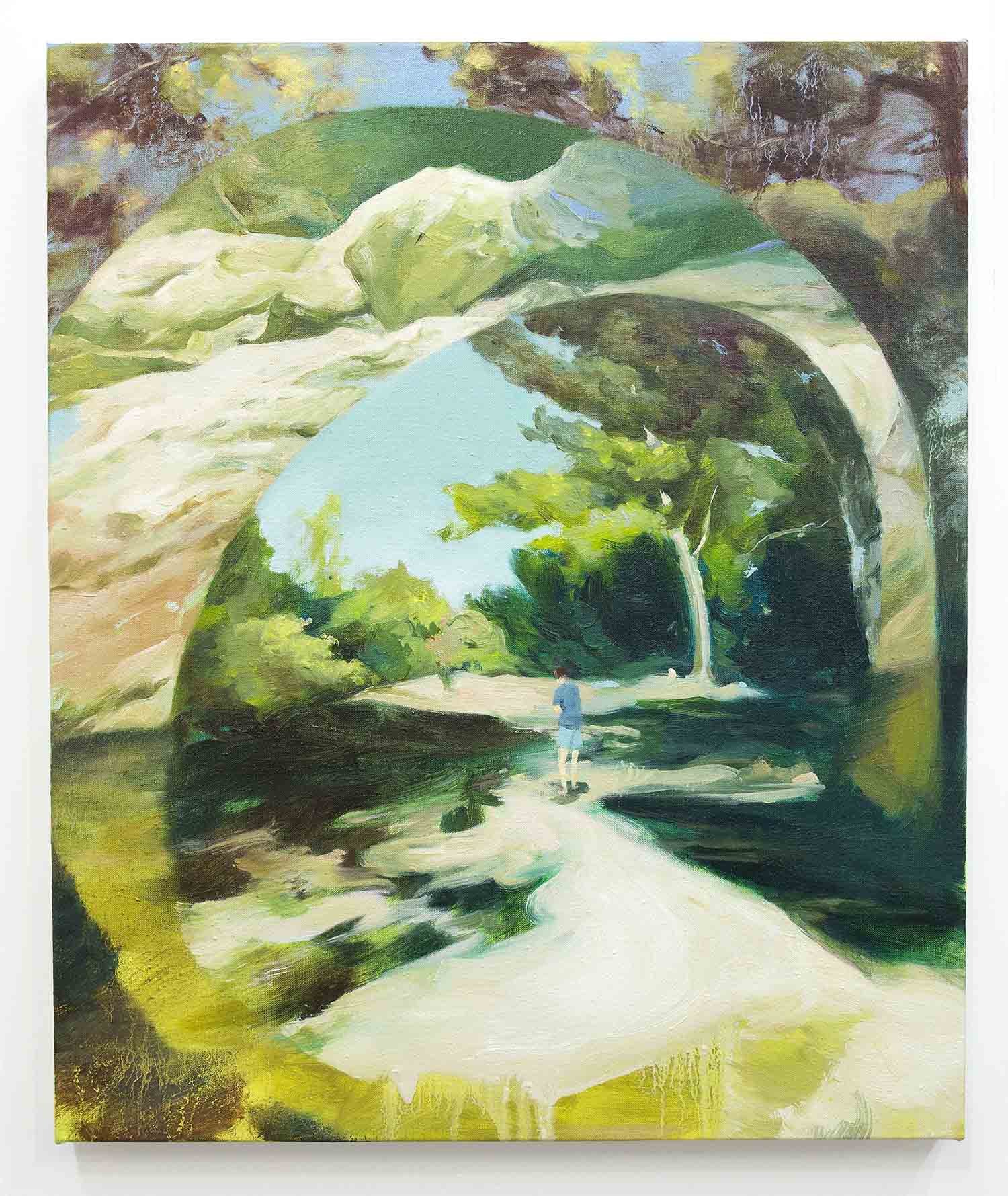

Conduit (it’s all just gone a bit coo coo), 2021, Paper, Galvanised steel, scaffolding clamps, latex, acrylic paint, spray paint, Dimensions variable

Site responsive installation exhibited as part of ‘Pigeon Park’ at Manor Place, Elephant and Castle. Supported by ‘This is Projekt’ curated by Christopher Stead, Joe Dennis and Stephen Burke

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: How do you explore architecture in the monumental in your work?

CR: There's a few things that I think about, I guess. Sometimes I respond to the architecture of the space itself, I'm quite drawn to in between spaces. I also think about how much sculpture can interact with the space, like imagining that it's going through the ceiling or going into the ground. I would not usually show my work on a plinth, for example unless that was a part of the work, sometimes the plinth is the work. Sometimes my sculptures move through a space as if escaping or leaving the room, eating and tunnelling, going through a wall or into the ground, connecting spaces. So they've become quite performative in that sense. There's always a sense of my sculptures moving through a space, inviting the viewer to imagine a space beyond the walls. They become the architecture that you don't necessarily see. The last thing I did for a show in Catford they went through office ceiling tiles that felt like the sculptures had grown into the space like trees. It made it look like it was propping up the ceiling. I like this idea of something being bigger than the space, living in London you feel quite confined by space and time. Squashing a big sculpture in a smaller space can subvert perception and make it feel bigger, whereas, when I have done larger things in warehouses, suddenly your sculpture feels really small. The sculpture I made in Oslo was almost seven metres tall!

DA: Wow! That’s incredible.

CR: It was a really well supported residency with amazing technical support. The residency was in between my first and second year of my MA at the Royal College of Art, and I had to come back and think, Okay, so how do I fit this kind of work into my small studio? It was then that they started to bend and twist and look as though they were going through the wall. I'm drawn to weird and crumbling spaces as well. Doing work in dusty warehouses informs my work and then I can take that and put it into a regular white cube gallery setting. Recently I’ve had to show in more conventional spaces. So that's been quite weird for me.

Install shot of Catriona’s work ‘Rude Enormous Monoliths’ 2022 in ‘Lost in a Just-in-Time Supply Chain’ curated by Josh C Wright at Peacocks in Catford, Hypha Studios, Photo: Rob Harris

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: Could you speak more about your approach to materials within your work?

CR: I love materials and getting messy. I use a combination of things. As I mentioned earlier, I collect discarded and reclaimed materials. Sometimes I'm really drawn to collecting flooring and roofing, discarded building or domestic materials. I like contrasting things that look a bit squishy with my hard cast surfaces. I'm obsessed with the idea of aggregate at the moment, as well as mixing things into my casts. I work a lot with concrete and that's where this idea of aggregate comes from. It's a conflicting material to work with sustainably. I've read quite a lot of things about concrete, I’m obsessed with how the Colosseum lasted such a long time. This long lost recipe of concrete that is so durable that it can outlive a civilisation, but yet contemporary modern concrete is perceived as so precarious. It’s weak and we often demolish it. It cracks because we haven’t taken care of it and we treat it like a throwaway material. I’ve started mixing my paper into my concrete and making it much lighter and to reduce the amount of concrete that I'm using, and the paper erodes away leaving cracks and gaps. The lightness means I'm able to be a bit more playful with it. It can alter people’s perception of my sculptures as it looks like I've made this really heavy object but it's actually quite lightweight, it can make you do like a double take, especially when it looks like it is going to collapse. I've started working with paper pulp and papier-mâché a lot as well and making it look a lot like concrete. I’m going back to that idea of monumentality, how does something look like it's monumental when it's actually made of newspaper or something else that looks heavy. I flip between different materials depending on what I'm doing. For The Factory Project show that I did last year, which was curated by Thorp Stavri, I made this giant concrete slab that was actually made out of papier-mâché. It got lifted on top of my scaffolding sculpture that had other real concrete elements on the ground. I suppose it’s a bit of a facade in a way.

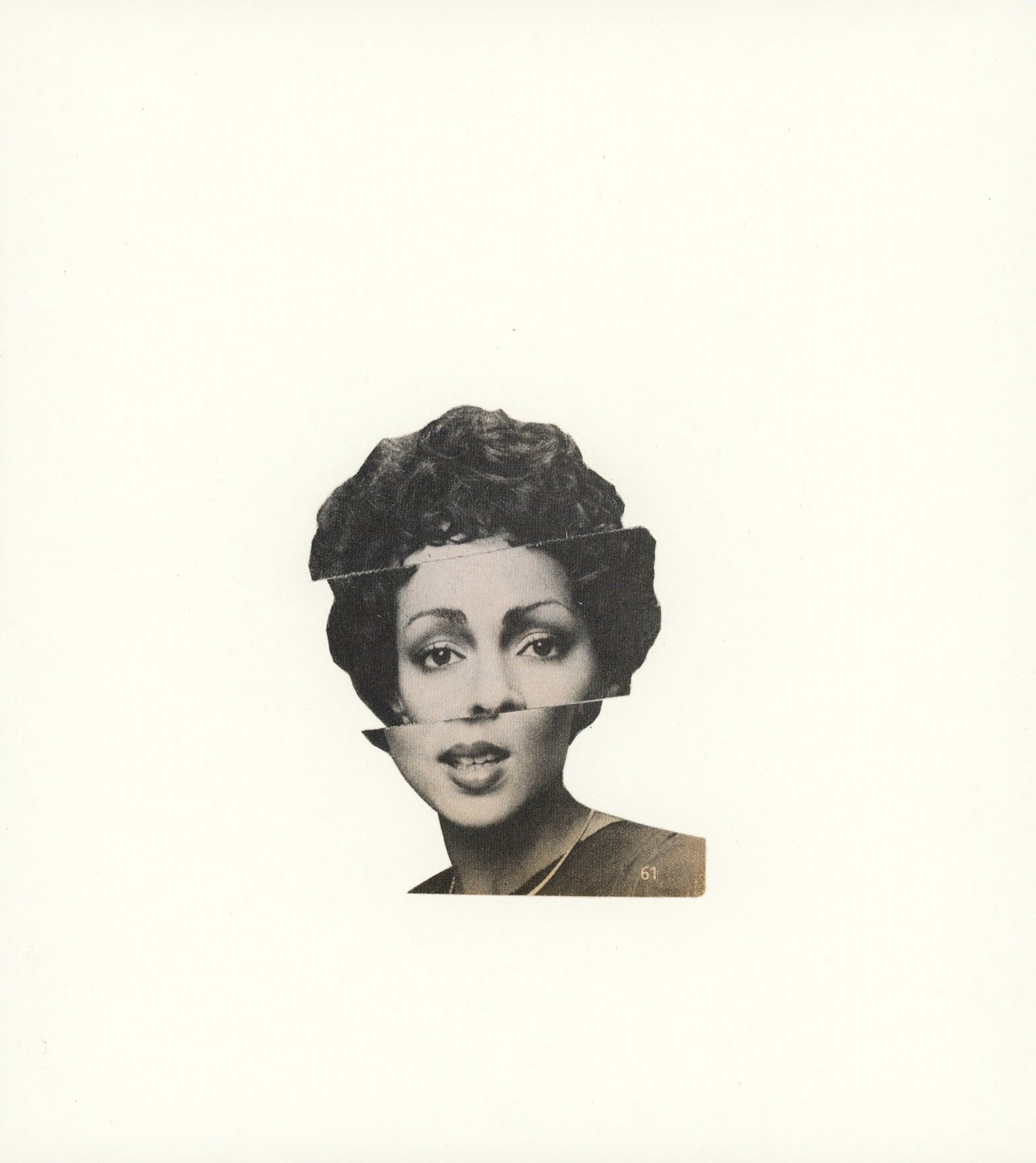

Close-up of Fissility, 2021, 90cm x 110cm x 15cm, Paper-clay, newspaper pulp, cardboard pulp, clay, acrylic paint, reclaimed perspex, ratchet strap, Photo: Catriona Robertson

Exhibited at the Muse Gallery, Winter Show January 2022

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: It's really interesting to have that layer of playfulness and facade or deception within the materiality of the work itself.

CR: I like the idea of casting as well, because I don't always know exactly how it's going to turn out. There's a lot of experimentation with the layering up of materials, and sometimes by mixing different materials together I can create cracks and eroded surfaces, but also some polished surfaces depending what aggregate I mix in. I work a lot with layers. At the moment, they're kind of turning into paintings. You're always working in reverse and then there's a big reveal at the end.

DA: A nice surprise! How do your sculptures relate to your own body?

CR: There's something quite fun about how I play with the weight. I’d like to play around with that more. I like making something bigger than myself and I really like being on ladders! Recently I have started to occasionally perform with my sculptures. I did a sleeping performance with the work I made for the ‘Terra Nexus’ show last year and for my show ‘Underlay’ at Set Studios. I started lying down next to my sculptures, because I began to feel that they were becoming quite immersive, as they have become more bendy and architectural in the way that I was moving around them. I just wanted to lie underneath them and look up at them for a moment. That makes you feel quite small and they also have this sense of precariousness about them sometimes. People think that they're going to fall down. They look like they're going to collapse. Sometimes I climb on top of my sculptures as well, but I wouldn't let anyone else do it. With the sleeping performance, partly I was tired, but I was imagining this idea of sleeping through time and sinking into the ground, becoming part of the work in this new sediment layer in the Anthropocene. There is a limit to my own capabilities as well. I like to make things that fit exactly through the door and that flat pack, things that I can install and deconstruct myself. I try to do things within my own reach to a certain extent, but they have started to get bigger lately which become problematic!

'Sleeping Performance': ‘Dreaming of the Underland’ and what signatures we might leave on the Deep Time Strata. I could just lie here for a million years and let myself sink into the ground, sealed over by concrete’, Set Studios, Woolwich, 2021

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: That's such an important practical thing to consider. When you show a sculpture or installation again and put it back together in a new location, does it stay the same or change?

CR: It’s quite hard actually to put it all back together in the same way. That's something I've had to think more about lately. The work only exists for that exhibition period, a lot of the time, which is quite a difficult thing to deal with emotionally, and sometimes physically too. There's a temporality to these giant structures. It can be exhausting, but also difficult to repeat. They respond to different spaces so they do take on a different form. Sometimes I get new materials as well, but some elements stay the same. I’ve got really good at working out what pieces go where and what angles fit together. I can gauge a space and gauge how I’ll need to rebuild the structure, but sometimes there’s an extra 50cm you have to add on!

DA: It sounds like a lot of work! How did you find that the pandemic affected your practice?

CR: I just stopped to be honest. I didn’t go into my studio and I started redecorating my flat. I think I really needed a break. I found it quite challenging at first. I tried to do a few paintings here and there, and drawings. I taught myself a few things on Rhino, 3D modelling software, and updated my website which has since helped me with designing larger installations. I did a residency in the Old Central Saint Martins building in Holborn which was early on in the pandemic. It was so eerie as London was so empty. I spent my time exploring as they’d demolished half of the building. I didn’t end up doing much apart from drawing and photography as I was in awe of the place and a bit lost and confused. It was a place to contemplate. Sometimes it’s important to look at your surroundings to get inspired even if it’s not obvious what will come out of it immediately.

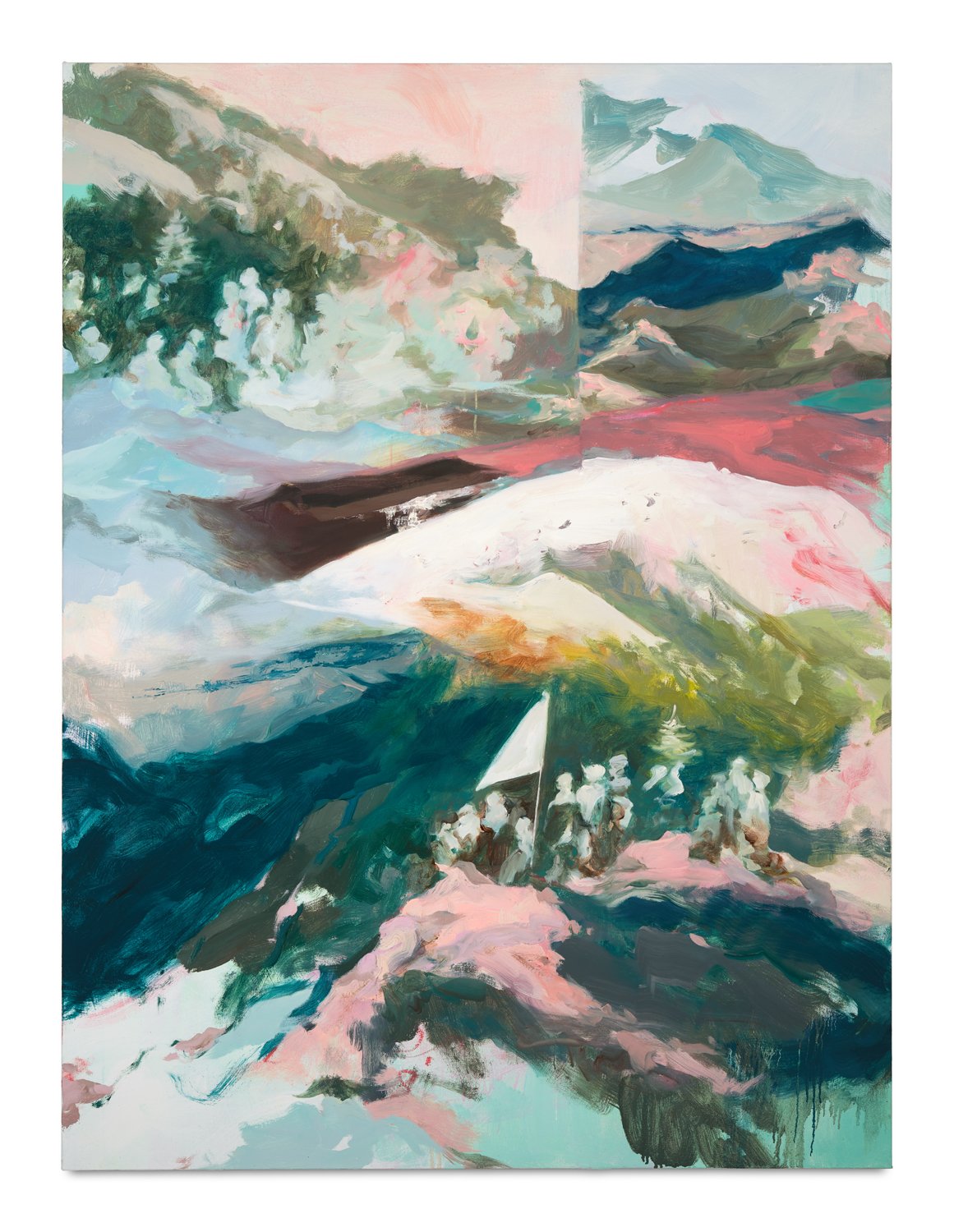

Burrow Sprout Grow, 2021, Concrete, paper-concrete, timber, plywood, resin, plastic, cardboard, foam underlay, corrugated roofing, window foil, carpet, lino, 90cm x 90cm x 260cm, Photo: Catriona Robertson

Exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery in London, Second Prize UK New Artist of the Year 2021, supported by Robert Walters Group

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: What would you like people to get from your work?

CR: I'm not sure. They can think whatever they want to. I'm open to ideas, but I suppose there's a sense of reclaiming materials and reclaiming the landscape, particularly for the work I’m making at the Merz residency. Maybe there's a sense of rebirth or elation too.

DA: Am I right in thinking you often reuse materials from old installations for new work?

CR: Yes. I’m thinking about this idea of reuse and I am a bit of a hoarder too! People tend to throw things away very quickly, and I’m interested in how you can recycle, reuse or adapt something. That reuse is not always entirely visible in my work as things are often embedded in the surface of sculptures.

DA: Have you had any surprising or memorable reactions to your work?

CR: There was a really good comment from my friend's son. He responded to the piece exhibited at The Factory Project. He said, ‘If this was a roller coaster, it would make me feel sick’. I thought that was so fantastic and makes it seem more playful.

DA: Yes! Whose work inspires you? You mentioned Kurt Schwitters earlier, but is there anyone else that really stands out?

CR: I love Phyllida Barlow, she’s a big inspiration for me. I’m always amazed at how she creates her monumental work. I guess there's a lot of comparison with our practices in terms of deconstruction and reconstruction.

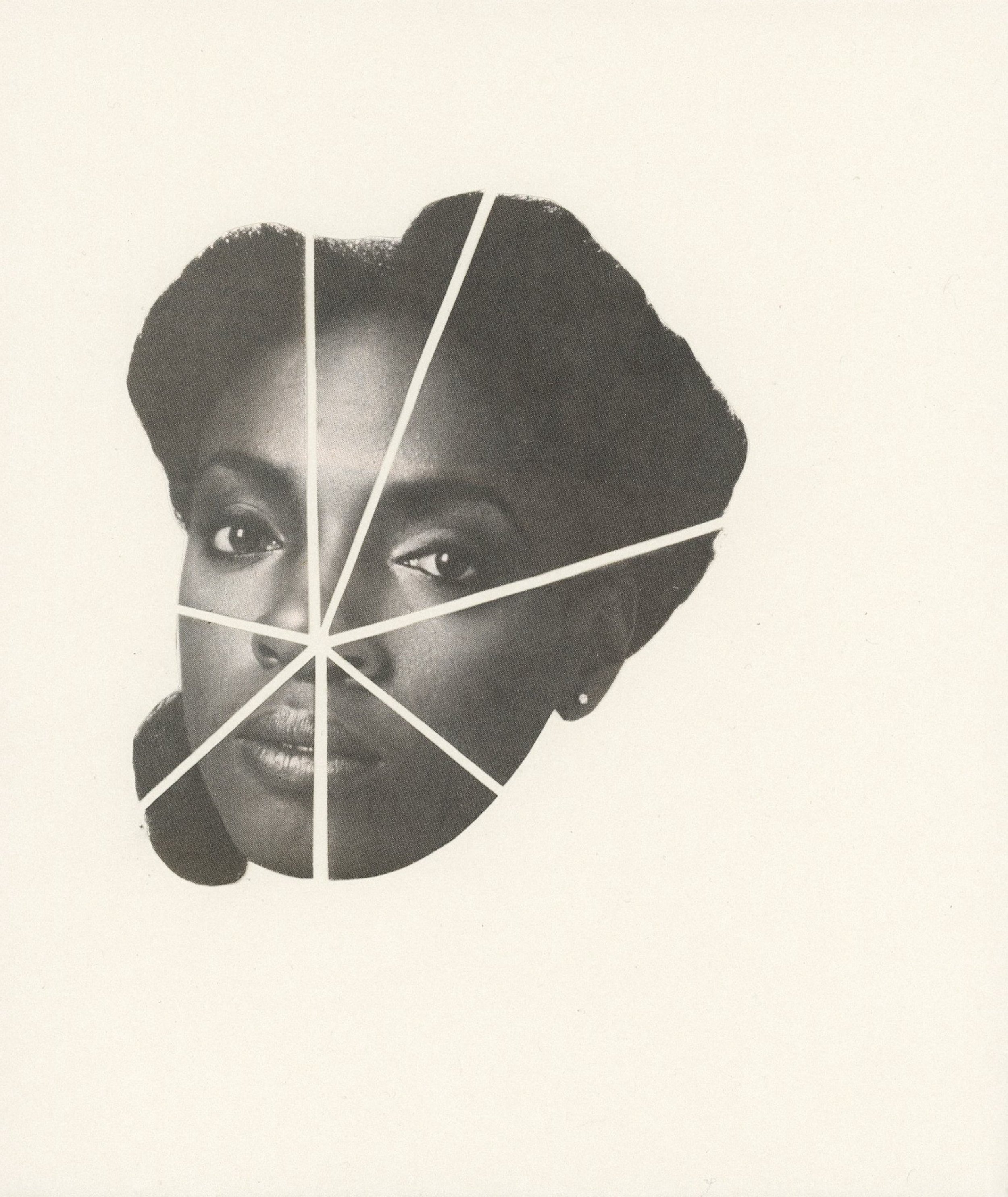

Fissility: Holding it all together, 2021, Paper-concrete, paper-clay, galvanised steel, clamps, reclaimed perspex, resin, acrylic paint, spray paint, ratchet straps, Dimensions variable, Photo: Thorp-Stavri

Site responsive installation as part of ‘The Factory Project’ curated by Thorp-Stavri

Photo courtesy of the artist

DA: Yeah, definitely the monumentalism of her work.

CR: Yeah. She's always recycling her work. I think she has a graveyard of her old sculptures. I was really amazed by the kind of heights her work can reach and she just doesn't care how messy the work is. It's got this unfinished quality to it. I don't think I'll ever finish anything either. Everything is ongoing.

DA: Apart from the residency you’re currently on, are there any other projects that you're working on?

CR: Yeah, I'm working on an exhibition at Tension Fine Art in Penge at the moment. I'm also taking time to work on my professional artistic skills as part of the year long mentorship from the Royal Society of Sculptors Gilbert Bays Award. It's been really good. There'll be a show at the beginning of next year and I need to start thinking about what I’m going to make.

DA: I look forward to seeing what you make in the future. Thanks so much Cat!

CR: Thank you so much.